State-of-the-art Code Generation with AlphaCodium – From Prompt Engineering to Flow Engineering

TL;DR

Code generation problems differ from common natural language problems – they require matching the exact syntax of the target language, identifying happy paths and edge cases, paying attention to numerous small details in the problem spec, and addressing other code-specific issues and requirements. Hence, many of the optimizations and tricks that have been successful in natural language generation may not be effective for code tasks.

In this work, we propose a new approach to code generation by LLMs, which we call AlphaCodium – a test-based, multi-stage, code-oriented iterative flow, that improves the performances of LLMs on code problems.

We tested AlphaCodium on a challenging code generation dataset called CodeContests, which includes competitive programming problems from platforms such as Codeforces. The proposed flow consistently and significantly improves results.

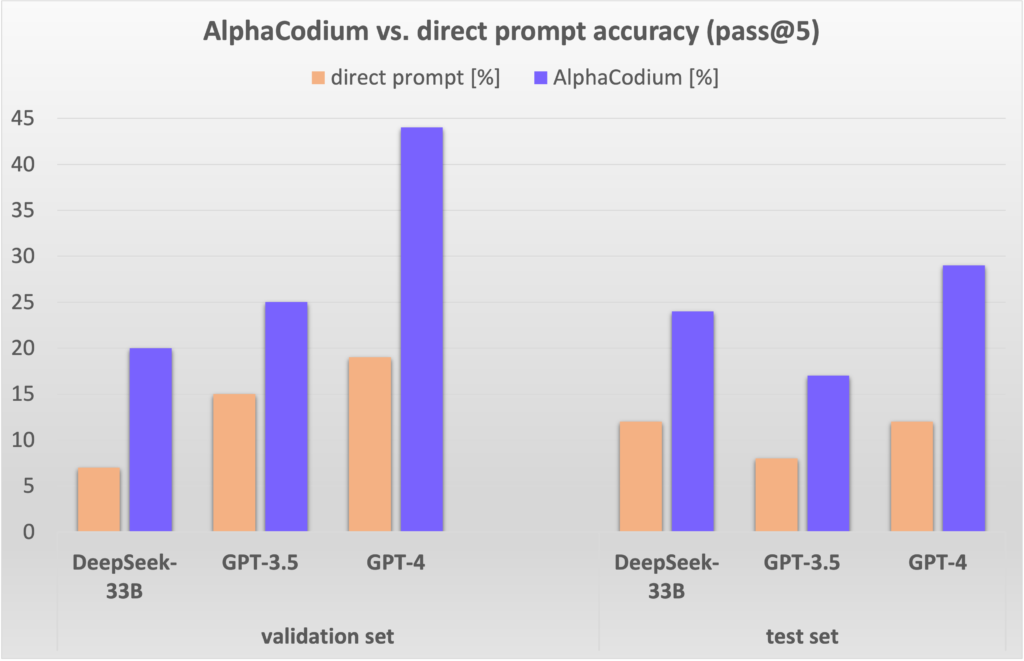

On the validation set, for example, GPT-4 accuracy (pass@5) increased from 19% with a single well-designed direct prompt to 44% with the AlphaCodium. AlphaCodium also outperforms previous works, such as AlphaCodium, while having a significantly smaller computational budget.

Many of the principles and best practices acquired in this work, we believe, are broadly applicable to general code generation tasks.

In our very new open-source on [icwcount-github-alpha-codium] we share our AlphaCodium solution to CodeContests, along with a complete reproducible dataset evaluation and benchmarking scripts, to encourage further research in this area.

CodeContests dataset

CodeContests is a challenging code generation dataset introduced by Google’s Deepmind, involving problems curated from competitive programming platforms such as Codeforces. The dataset contains ~10K problems that can be used to train LLMs, as well as a validation and test set to assess the ability of LLMs to solve challenging code generation problems.

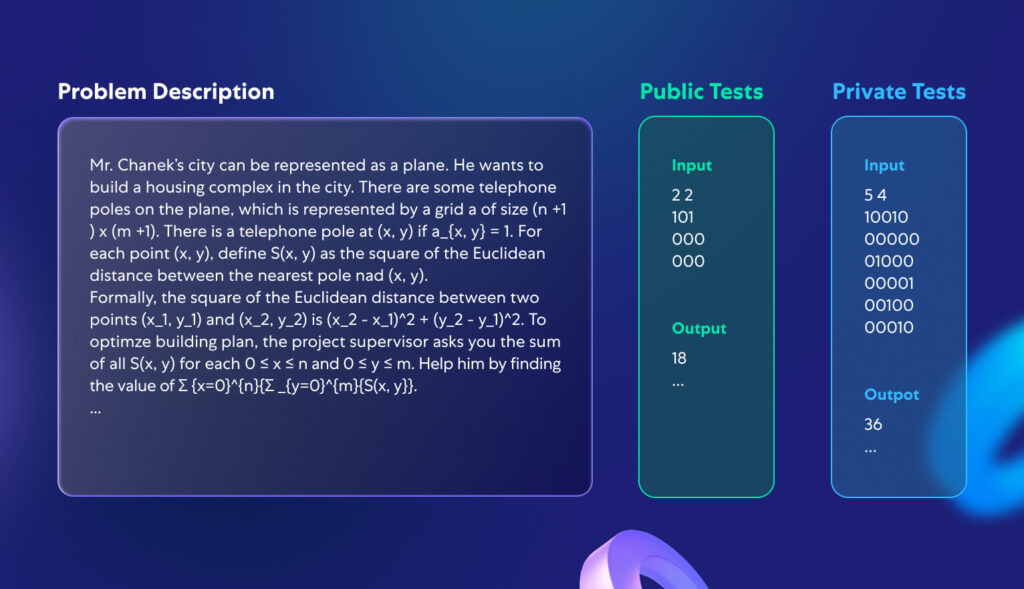

In this work, instead of training a dedicated model, we focused on developing a code-oriented flow, that can be applied to any LLM pre-trained to support coding tasks, such as GPT or DeepSeek. Hence, we chose to ignore the train set, and focused on the validation and test sets of CodeContests, which contain 107 and 165 problems, respectively. Figure 1 depicts an example of a typical problem from CodeContests dataset:

Each problem consists of a description and public tests, available as inputs to the model. The goal is to generate a code solution that produces the correct output for any (legal) input. A private test set, which is not available to the model or contesters, is used to evaluate the submitted code solutions.

What makes CodeContests a good dataset for evaluating LLMs on code generation tasks?

- CodeContests, unlike many other competitive programming datasets, utilizes a comprehensive private set of tests to avoid false positives – each problem contains ~200 private input-output tests the generated code solution must pass.

- LLMs generally do not excel at paying attention to small details because they typically transform the problem description to some “average” description, similar to common cases on which they were trained. Real-world problems, on the other hand, frequently contain minor details that are critical to their proper resolution. A key feature of CodeContests dataset is that the problem descriptions are, by design, complicated and lengthy, with small details and nuances (see a typical problem description in Figure 1). We feel that adding this degree of freedom of problem understanding is beneficial since it simulates real-life problems, which are often complicated and involve multiple factors and considerations. This is in contrast to more common code datasets such as HumanEval, where the problems are easier and presented in a concise manner. An example of a typical HumanEval code problem appears in Appendix 1.

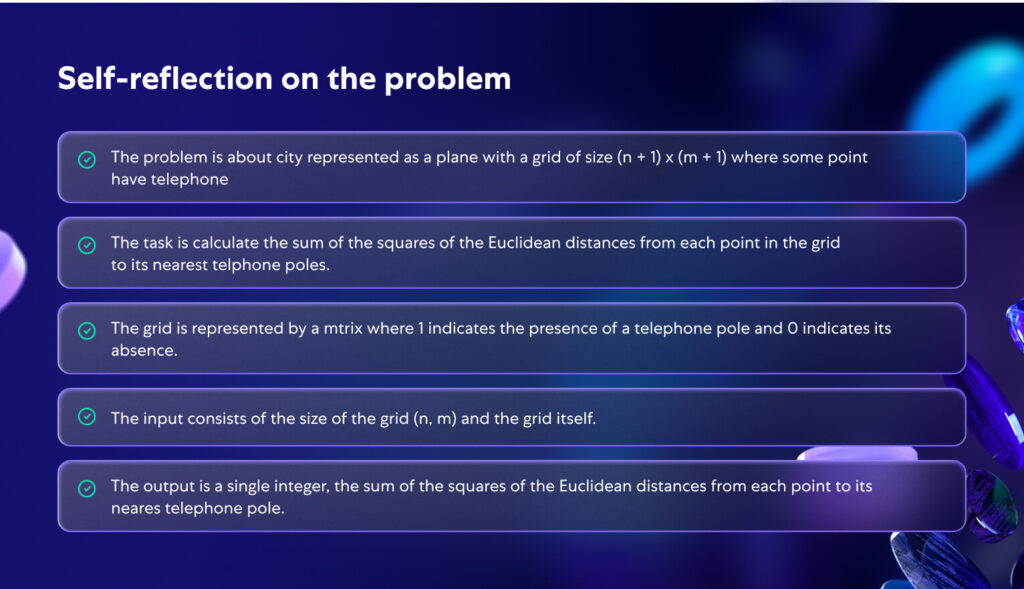

Figure 2 depicts the model’s introspection on the problem presented in Figure 1. Note that proper self-reflection makes the problem clearer and more coherent. This illustrates the importance of problem understanding as part of a flow that can lead with high probability to a correct code solution.

The proposed flow

Due to the complicated nature of code generation problems, we observed that single-prompt optimizations, or even chain-of-thought prompts, have not led to meaningful improvement in the solve ratio of LLMs on CodeContest. The model struggles to understand and “digest” the problem and continuously produces wrong code, or a code that fails to generalize to unseen private tests. Common flows, that are suitable for natural language tasks, may not be optimal for code-generation tasks, which include an untapped potential – repeatedly running the generated code, and validating it against known examples.

Instead of common prompt engineering techniques used in NLP, we found that to solve CodeContest problems it was more beneficial to employ a dedicated code-generation and testing-oriented flow, that revolves around an iterative process where we repeatedly run and fix the generated code against input-output tests. Two key elements for this code-oriented flow are (a) generating additional data in a pre-processing stage, such as self-reflection and public tests reasoning, to aid the iterative process, and (b) enrichment of the public tests with additional AI-generated tests.

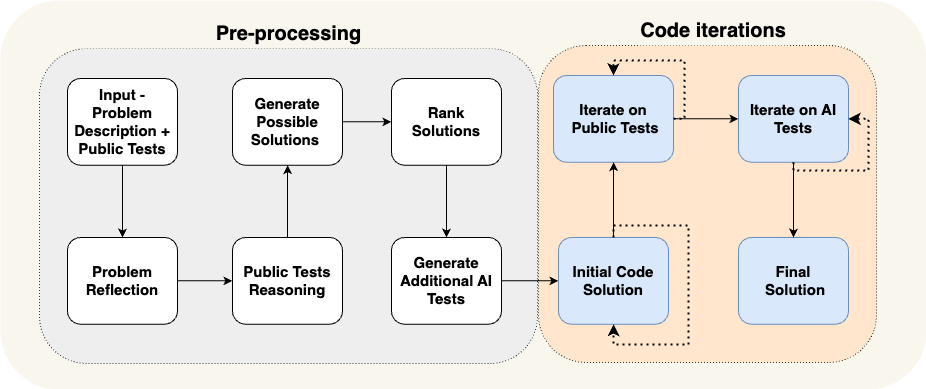

In Figure 3 we present our proposed flow for solving competitive programming problems:

The flow in Figure 3 is divided into two main phases:

– The pre-processing phase represents a linear flow where we reason about the problem, in natural language.

– The code iterations phase includes iterative stages where we generate, run, and fix a code against certain tests.

In Table 1 we review the different stages:

| Stage name | Task |

| Problem Reflection | Describe the problem, in bullet points, while addressing the problem goal, inputs, outputs, rules, constraints, and other relevant details. |

| Public Tests Reasoning | Explain why each test input leads to the output. |

| Generate Possible Solutions | Generate a list of 2-3 possible solutions to the problem, described in natural language. |

| Rank Solutions | Rank the possible solutions and choose the “best solution”, in terms of correctness, simplicity, and robustness. (not necessarily take the “most efficient” solution). |

| Generate Additional AI Tests | Generate an additional 6-8 diverse input-output tests for the problem. Try to cover cases and aspects not covered by the original public tests. |

| Initial Code Solution | The goal of this stage is to generate an initial code solution to the problem. It is essential this code will be as close as possible to the correct code, so the run-fix iterations in the next stages will have a better chance of succeeding. The stage flow: – Choose a potential solution. Generate a corresponding code, and run it on selected public and AI tests. – Repeat this process until the tests pass, or until a try-limit is reached. – The first code that passes the tests, or the code with the closet output, will be used as the base code for the next steps. |

| Iterate on Public Tests | Start from the base code. Iteratively run it on the public tests. If the code fails on a specific test, try to fix it, given the error message. |

| Iterate on AI-generated Tests | Continue the run-fix iterations on the AI-generated tests. Use “test anchors” (see next section) |

Additional intuition and insight into the proposed flow:

Knowledge accumulation – we try to progress from easy to difficult, gaining knowledge and insight along the way to help with the more difficult stages. For example, the first step, self-reflection, can be utilized as input to more difficult steps like generate possible solutions. The pre-processing phase’s outputs are used to aid the most challenging and critical phase, code iterations, where we actually try to generate code that correctly solves the problem.

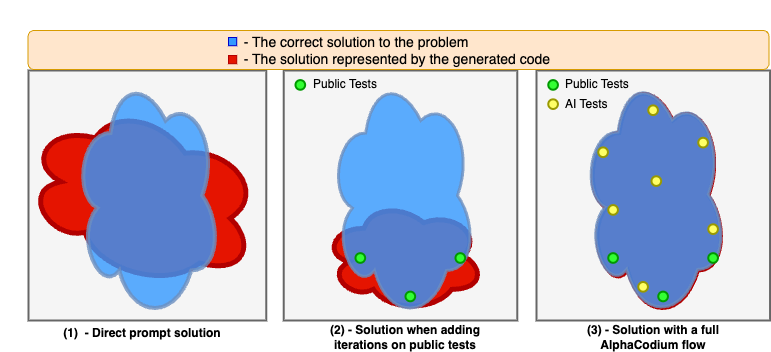

Generating additional AI tests is easier than generating a full solution code – generating additional tests requires mainly understanding the problem and basic brute-force or logical reasoning. There is no need to fully “solve” the problem in order to generate additional useful input-output test pairs. This is in contrast to generating a correct solution code, which requires a complete algorithmic solution, equivalent to correctly solving any possible pair of input-output tests. As a result, we can generate more AI tests, and then leverage them to improve the code creation phase, as described in Figure 4. We further amplify the contribution of these additional tests by asking the model to focus on aspects not addressed by the original public tests, such as large inputs, edge cases, and so on.

Steps can be combined into a single LLM call – the flow described in Figure 3 is a conceptual flow, emphasizing the process’s high-level steps. In practice, structured output (see next section) enables to combine multiple stages into a single LLM call, in order to save resources, or because a model performs better when doing specific tasks concurrently.

Code-oriented design concepts

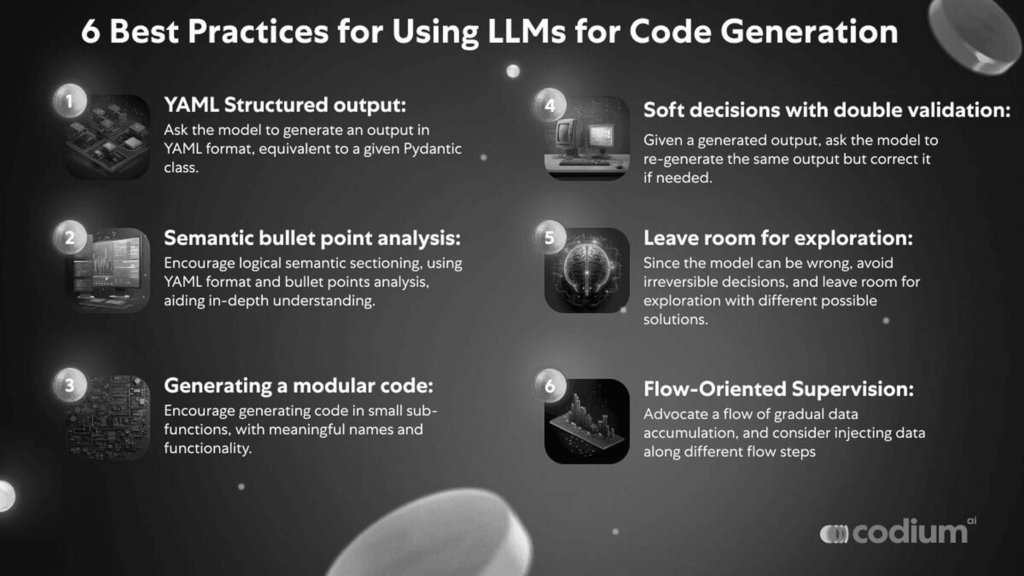

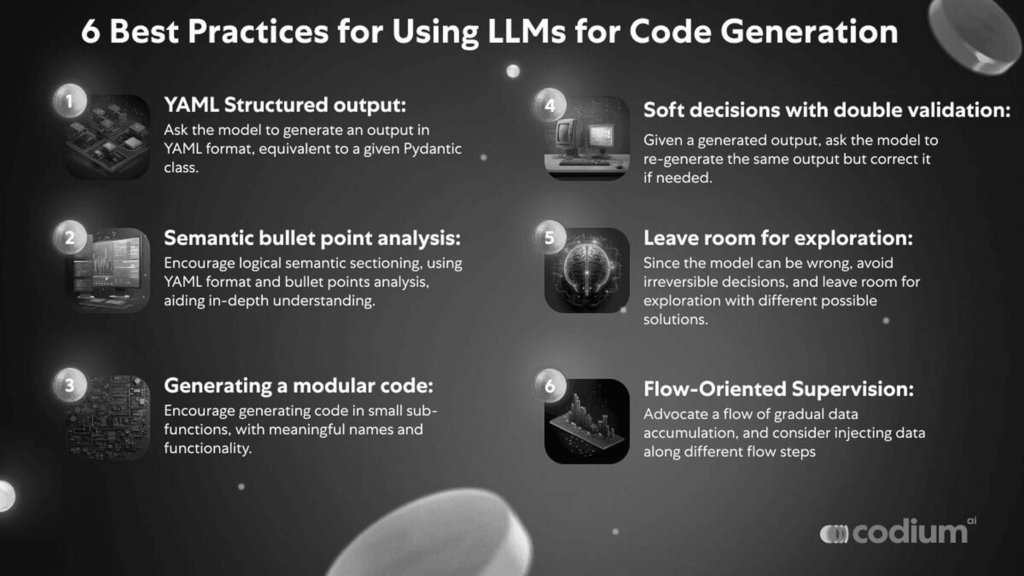

In this section, we will present several design concepts, tricks, and best practices we found beneficial when trying to solve code generation problems. The AlphaCodium flow proposed in Figure 3 extensively uses these design concepts:

YAML structured output: the usage of structured output – asking the model to generate an output in YAML format, equivalent to a given Pydantic class – is a key component in our proposed flow. An example of such instruction:

... Your goal is to present possible solutions to the problem. Make sure that each solution fully addresses the problem goals, rules, and constraints. The output must be a YAML object equivalent to type $PossibleSolutions, according to the following Pydantic definitions: class Solution(BaseModel): name: str = Field(description="The name of the solution") content: str = Field(description="A description of the solution") why_it_works: str = Field(description="Why this solution is correct. Be specific and detailed regarding the problem rules and goals") complexity: str = Field(description="The complexity of the solution") class PossibleSolutions(BaseModel): possible_solutions: List[Solution] = Field(max_items=3, description="A list of possible solutions to the problem. Make sure each solution fully addresses the problem rules and goals, and has a reasonable runtime - less than three seconds on a modern computer, given the problem constraints for large inputs.")

Structured output eliminates the majority of the hassle and dark knowledge required for “prompt engineering”, and instead allows complicated tasks to be presented in a straightforward, code-like manner. It also makes it possible to obtain complex answers that involve several stages, representing a logical and methodical thinking process.

While newer versions of GPT have built-in support for JSON-style output, we argue that YAML output is far more suitable specifically for code generation tasks, see Appendix below.

Bullet points analysis – when asking an LLM to reason about an issue, a better result is usually obtained when demanding the output to be in bullet points format. Bullet points encourage an in-depth understanding of the problem, and force the model to divide the output into logical semantic sections, leading to improved results. For example, with self-reflection on a problem in bullet points (see Figure 2), each bullet point represents a semantic understanding of a different part of the problem – general description, goals and rules, input structure, and output structure.

LLMs do better when generating a modular code – when LLMs are asked to generate a single lengthy function, we observed poor results – the code often contains bugs or logical mistakes. Even worse, a single monolithic code hurts the ability to perform iterative fixing – the model struggles to pinpoint and fix problems, even when given the error message.

When clearly asking the model to: “divide the generated code into small sub-functions, with meaningful names and functionality”, we observe a better-produced code, with fewer bugs, and higher success rates for the iterative fixing stages.

Soft decisions with double validation – LLMs tend to struggle with code tasks that require them to think, reason, and make strict, non-trivial decisions. Let’s take for example the task of generating additional tests for a problem. Quite often, some of the tests the model will generate will be plain wrong. With a double validation process, we add an extra step where, given the generated output, the model is asked to re-generate the same output, but correct it if needed. For example, given the generated AI tests as input, the model is asked to re-generate the same tests, while correcting wrong output, if exists. We found that this step of double validation, while encouraging the model to be critical and to reason, is more effective than asking a direct yes\\no question: “is this test correct?”

Postpone decisions, try to avoid direct questions, and leave room for exploration – when we ask the model direct questions regarding complicated issues, we consistently see hallucinations and wrong answers.

Hence, similarly to Karpathy’s messages in the below tweets, we adopt a flow of gradual data accumulation, from easier tasks to harder ones:

– Start with the easiest task – self-reflection on the problem, and reasoning about public tests.

– Move to generating additional AI tests, and possible solutions to the problem

– Only after we acquire the model’s answers to the tasks above, we move to actual code generation, and run-fix iterations.

As another example, instead of choosing a single algorithmic solution to the problem, we prefer to rank several possible solutions, and give priority, but not exclusiveness, to the top-ranked solution when generating initial code. Since the model can be wrong, it’s better to avoid irreversible decisions, and leave room for exploration and code iterations with different possible solutions.

Test anchors – even with double validation, some AI-generated tests will be wrong. This makes iterations on them challenging – when a test fails, how can we know if it is because the code is wrong, or because the test is wrong? When we ask the model directly “who is wrong”, we often see hallucinations, and may end up with a wrongly fixed code. To tackle this problem, we utilized a technique of “test anchors”:

– Iterate first on the public tests, which we know are correct. When finished, set all the passed tests as anchor tests.

– Now iterate on the AI-generated tests, one by one. If a test passes, add it to the list of test anchors

– If a test fails, assume it’s because the code is incorrect, and try to fix the code. However, demand that the fixed code also passes all the test anchors already acquired. As a result, the test anchors will protect us against an incorrectly fixed code.

Another optimization for test anchors is to sort the AI-generated tests from easy to hard. That way, there are more chances that the iterative process will acquire anchors at the beginning of the process, which can be used as protection later when iterating on the more complicated AI tests, where the chances of a wrong test output are higher.

Results

Direct prompt Vs AlphaCodium

In Figure 5 we compare AlphaCodium results to the results obtained with a single well-designed direct prompt. The metric being used is pass@k, defined as the percentage of problems solved by using k generated solutions per problem.

As can be seen, AlphaCodium consistently and significantly improves the performance of LLMs on CodeContests problems. This is true both for open-source (DeepSeek) and close-source (GPT) models, and for both the validation and test sets.

Comparison to other works:

In Table 3 we compare AlphaCodium results of other methods from the literature.

| model | set | method | score |

| GPT-3.5 | validation | AlphaCodium (pass@5) | 25% |

| CodeChain (pass@5) | 17% | ||

| test | AlphaCodium (pass@5) | 17% | |

| CodeChain (pass@5) | 14% | ||

| GPT-4 | validation | AlphaCodium (pass@5) | 44% |

| DeepMind fine-tuned | validation | AlphaCodium (pass@10@1K) | 17% |

| AlphaCodium (pass@10@100K) | 24% | ||

| GPT-4 | test | AlphaCodium (pass@5) | 29% |

| DeepMind fine-tuned | test | AlphaCodium (pass@10@1K) | 16% |

| AlphaCodium (pass@10@100K) | 28% | ||

| Gemini-pro | AlphaCode2: No comparable results reported on an available version of CodeContests. According to the AlphaCode2 technical report, where the authors compare AlphaCodium with AlphaCode2 results on an unpublished dataset, AlphaCodium achieves similar results (29%, pass@10) to AlphaCodium when using 4 orders of magnitude less of LLM calls (@100). | ||

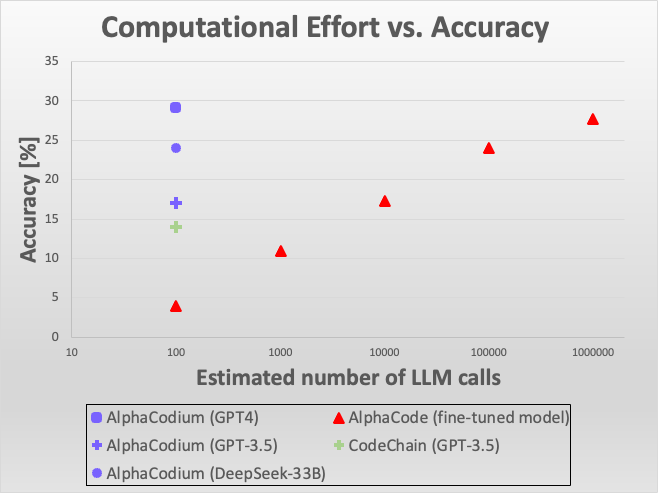

Accuracy vs LLM calls comparison between AlphaCodium to other solution. While AlphaCodium achieves similar accuracy in comparison to AlphaCodium, it it used 4 order of magnitude less of LLM calls.

As can be seen, when comparing AlphaCodium to CodeChain with the same model (GPT-3.5) and the same metric (pass@5), AlphaCodium consistently does better.

When comparing to AlphaCodium work, we need to take into account that AlphaCodium uses a different generation methodology – fine-tuning an (unknown) model specifically for code problems, generating a very large number of code solutions, clustering them, and submitting K solutions from the top clusters. pass@10@100K, for example, means the 100K (!) solutions were generated and clustered, and 10 solutions were finally chosen and submitted. AlphaCodium used a fine-tuned model, and utilized a brute-force-like approach with a significantly higher number of LLM calls. Yet, the top results achieved by AlphaCodium are better

Also note that neither AlphaCodium nor CodeChain released a reproducible solution, including an end-to-end evaluation script. There are subtleties when evaluating results. For example – how to treat problems with multiple solutions, how to address tolerance issues, timeouts, and more.

We compare to the numbers reported in the papers, but release a full reproducible code and evaluation script in order to enable future comparisons to be more reliable and reproducible.

Computational effort and comparison to AlphaCodium and AlphaCode2:

AlphaCodium performs ~15-20 LLM calls per solution, so a pass@5 submission involves ~100 LLM calls.

AlphaCodium did not report how many LLM calls were done per run. Let’s assume one call per run was done (unknown, could be more), then a pass@10@100K (i.e. ten submissions, curated from 100,000 generated solutions) involves 1M LLM calls, four orders of magnitude more than AlphaCodium. Yet, the top results obtained by AlphaCodium are better.

See Figure 3. above which is visualizing these results.

Recently, a new work called AlphaCode2 was published (technical report), where a Gemini-Pro model was fine-tuned and evaluated on code programming problems. The paper also reported results on a CodeContests benchmark, but on an updated variant that they did not release to the public. According to AlphaCode2 report: “AlphaCode2 requires about 100 samples to reach the level of performance of AlphaCodium with a million samples, making it over 10000× more sample efficient.” Hence both AlphaCode2 and AlphaCodium are four orders of magnitude more efficient than AlphaCodium, LLMs call-wise.

But, AlphaCode2 utilized a modern foundation model that was heavily fine-tuned specifically for CodeContests competition, while AlphaCodium uses general-purpose models as-is, and improves their performances without extra data and an expensive training phase.

Appendix

1) Example of a HumanEval code problem:

/*

Check if in given vector of numbers, are any two numbers closer to each other than given threshold. >>>

has_close_elements({1.0, 2.0, 3.0}, 0.5) false >>>

has_close_elements({1.0, 2.8, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 2.0}, 0.3) true

*/

#include<stdio.h>

#include<vector>

#include<math.h>

using namespace std;

bool has_close_elements(vector<float> numbers, float threshold){

We can see that the problem is quite simplistic, without a lot of small details and nuances that a model needs to reason about.

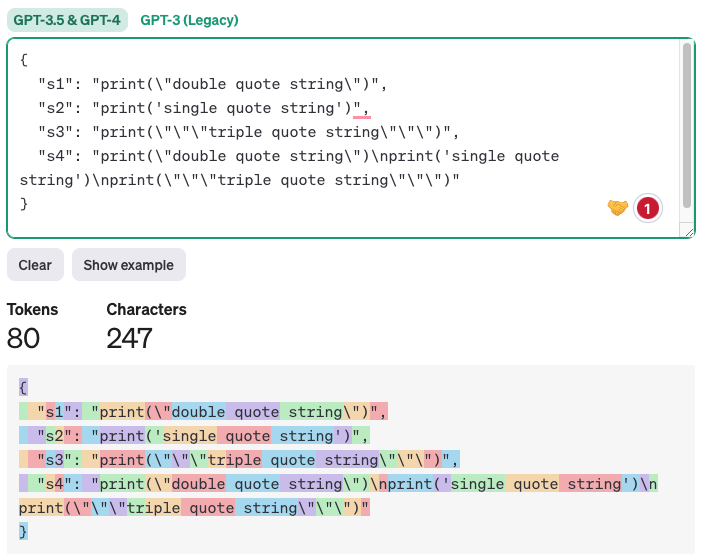

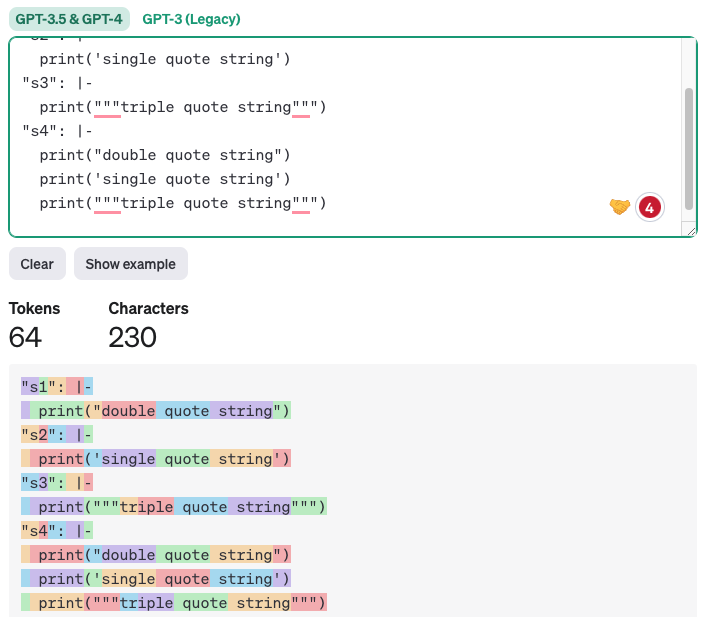

2) Why YAML output is better suited for code generation tasks than JSON output

While newer GPT versions have inherent support for JSON-style output, we argue that YAML output is far better for code generation.

Why – generated code often contains single-quote, double-quote, special characters, and so on. LLMs will struggle to validly place these characters inside a JSON format, since a JSON output needs to be surrounded with initial double quotes. In contrast, YAML output with block scaler must only obey indention. Any text or code with proper indention will be a legal one.

In addition, YAML output has fewer tokens, hence reducing cost and inference time, and also resulting in increased quality as the model needs to pay attention to fewer tokens that are not essential.

An example of JSON vs YAML comparison (generated with https://platform.openai.com/tokenizer):

import json

import yaml

s1 = 'print("double quote string")'

s2 = "print('single quote string')"

s3 = 'print("""triple quote string""")'

s4 = f"{s1}\n{s2}\n{s3}"

# Create a dictionary with keys as variable names and values as the strings

data = {'s1': s1, 's2': s2, 's3': s3, 's4': s4}

# Convert the dictionary to a JSON-formatted string

json_data = json.dumps(data, indent=2)

print(json_data)

# Convert the dictionary to a YAML-formatted string, with block scalar style

yaml_data = yaml.dump(data, indent=2, default_style='|')

print(yaml_data)

Output:

JSON output:

YAML output:

Clearly, generating the code while maintaining only indention is simpler, more readable, and less error-prone.